To Repair The Humanist & Ethical Culture Movements, We Must Face History and Ourselves

16-minute read

-

Whiteness and Blackness, within the context of the United States, are socially constructed on the individual, systemic, and structural levels. The 17th-century architects who controlled land and financial markets realized that European laborers were necessary to ensure the extraction of our biosphere’s natural resources and continued subjugation and domination of the enslaved Africans, their descendants, and Indigenous peoples. Once binary racialization was codified into secular and religious laws, it proliferated through civil society, government mandates, and socio-cultural production and transmission. One way this violent legacy still manifests presently is through activated social dynamics in groups. Our society has become so habituated to these cultural norms that we are often not alerted to the stimuli or the impact of the social dynamic. Combined with our species’ in-group/out-group habits, socio-political conditions regarding overlapping crises, and individual variables, we can create collective conditions that harm other humans. Hannah Arendt warned us of the banality of evil, and Erik Fromm helped us to understand how the alienation of our current economic condition can manifest psycho-socially and physiologically. To change the world, our relationships with ourselves, others, and the planet must fundamentally change.

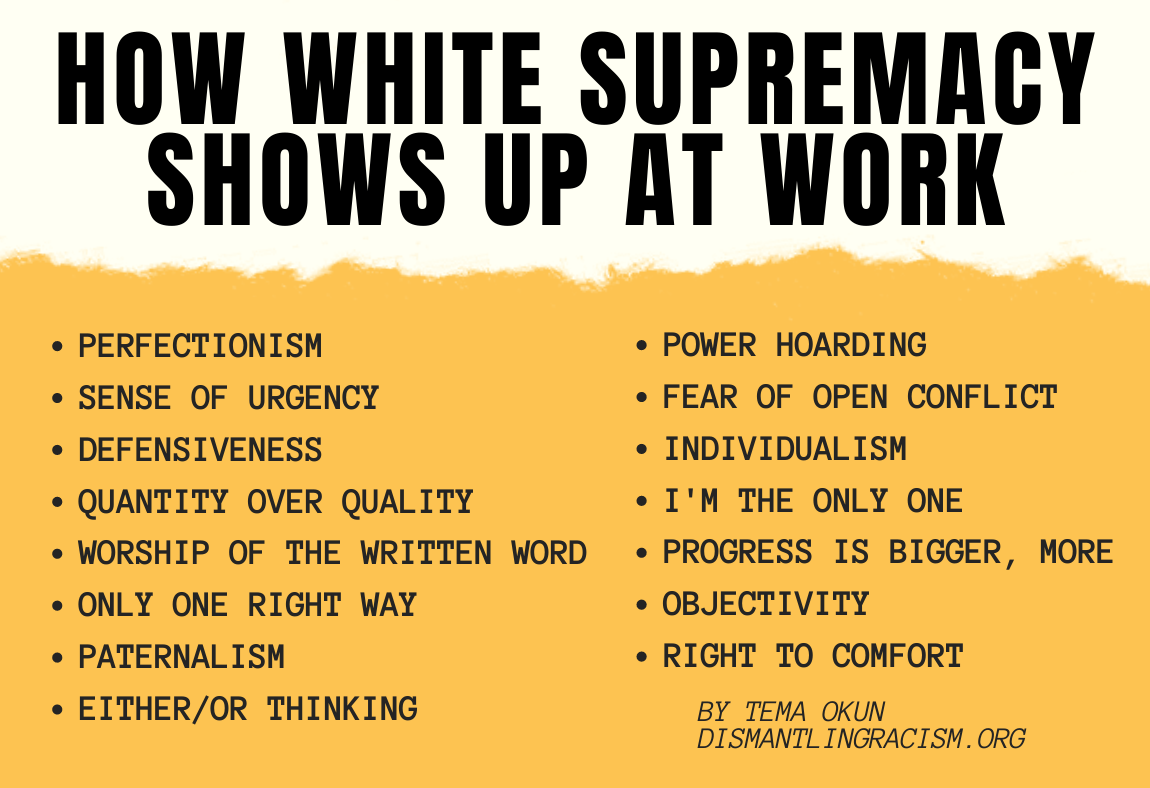

Dr. Tema Okun is an educator, writer, and activist who co-developed a 1999 article entitled “White Supremacy Culture” and re-released the article in 2021. Her intervention, informed by years of progressive community activism, attempts to help disrupt group habituation and make the social construct of Whiteness visible. If we allow the intervention, we can begin the work to build better human-centered systems and institutions that embrace difference and belonging.

Oftentimes people who’ve not been exposed to these historically documented facts have a variety of psychological and physiological reactions. These reactions are conditions as a result of intentional campaigns to advance disinformation, fracture multi-racial coalitions, and stall action on building a pluralistic society. These campaigns have effectively obfuscated the fact that sentient beings, poor, working poor, middle-class, and upper-class people (across race and gender) have more of a common shared struggle than we do with billionaires. While our differences do, in fact, matter and contribute to our lived realities— it should be our values and political commitments that anchor how we build and organize. Recently, these corporate-driven campaigns have utilized “identity politics” unmoored from its historical socio-political context to produce culture wars. These campaigns have effectively created conditions wherein our broad base coalition is unable to cooperate to address multiple overlapping crises created by the continued extractive and violent systems that maintain the wealth of a quarter of the world’s billionaires within the United States. The actors in this violent alliance and poorly hidden conspiracy to undermine the American project sit at the cross sections of mainstream religious interests, banks, land owners, and corporations. As a result of the intersections of power of these actors, “White Supremacy Culture” harms more than people of African or Indigenous descent or people with melanin phenotypic expression. The social phenomenon of “colorblindness,” Black capitalism, and other reforms to our current economic system do not adequately disrupt the power mechanisms wielded by the 720 billionaires inside the United States.

This “White Supremacy Culture” article can be one of many interventions groups can adopt to short-circuit habituation that undermines integrating people whose differences have been weaponized. Interventions are not long-term solutions. Hyperfocus on maladaptive habituation divorced from the political context can also threaten to stall social transformation. We must hold the tension of “living in multiple worlds” and continue to organize for new economic systems that allow for us to take action to ensure a thriving biosphere for ourselves and future generations, all the while continuing the collective work of realizing a truly democratic society.

In Solidarity,

Jasmine Banks

P.S.

This note was written in support of and in solidarity with Anya Overman. She continues to learn about herself and reckon with the realities of how her individual experiences link to broader political problems. As a result of what I’ve personally witnessed and experienced as an African American employee of the American Humanist Association, I am concerned my support of her could impact my work conditions. My note was not produced to publicly comment on the American Humanist Association but to address the resource in question. My values, principles, and commitments lead me to take this risk in order to maintain solidarity with Anya, her free expression of ideas, and my ancestral mandate to stand with those who speak truth to power in the face of corruption, oppression, and authoritarianism.

This is a conversation starter about how we can address white supremacy culture in these movements and evolve

I grew up attending the Ethical Society of St. Louis from age five, and I have worked in positions of leadership with multiple organizations in the humanist movement locally, nationally, and internationally over the course of 15 years.

In this piece, I share my observations of how white supremacy culture appears in these communities. Some of these observations have brought me or my colleagues harm. If you belong to any of these communities, please note this was not written to upset you. I wrote it to bring attention to specific, covert examples of systemic harm in the atheist, humanist, and Ethical Culture movements.

Try not to let your brain replace “white supremacy culture” with “racism”

When people hear the term “white supremacy culture,” the immediate image that comes to mind is white people mistreating people of color – racism. But that is merely one facet of white supremacy culture. White supremacy culture is so much more than individual acts of racism.

Unfortunately, white supremacy culture is far more insidious than we give it credit for. I’m afraid it’s not as simple as learning to recognize racism and committing to not doing racist things.

White supremacy culture shows up in how people conditioned to believe in the superiority of white cultural norms interact with each other. It shows up in each of us – every day – not just in our behaviors but in how we think and feel. That’s what cultural conditioning does – it permeates so deep into us that it roots itself in our conscious.

As I mentioned in What is White Supremacy Culture?, white supremacy culture works with norms of other systems of oppression. These systems all work together to affect our lives in ways many of us are unaware of. Yes, even in humanism and even in Ethical Culture.

While there are many examples of overt white superiority culture that I could discuss in this piece, I want to name the more covert and insidious examples. The volume of covert examples below should also point to the fact that there are many overt examples.

The following from Tema Okun are some ways white supremacy culture shows up in our organizations. These characteristics are damaging because they are used as norms and standards without being proactively named or chosen by the group. They protect white superiority thinking without calling it that. And again, these characteristics show up in the attitudes and behaviors of all of us: white people and people of color.

Here are Tema Okun’s examples of the above characteristics and antidotes to each. I highly recommend reading this.

Facing my own internalizations of white supremacy culture

Confronting white superiority culture within yourself is an ongoing practice. One of the ways that it shows up in me the most is through perfectionism and defensiveness.

I was raised a perfectionist. I had strict parents who expected straight A’s at school. I internalized that pressure as I got older and developed a harsh and constant inner critic. That inner critic got me through a 4-year degree in 3 years and helped me start my writing business. But this inner critic also feeds the chronic depression and anxiety I’ve struggled to manage since I was a teen.

I also project this criticism onto others. I expect a lot from people. I tend to hyperfocus on mistakes – whether mine or someone else’s – and can easily get carried away with conflating that mistake with “doing wrong and being wrong.” Others have noticed this about me and pointed it out to me, but the feedback often comes in the form of a “you’re being really negative” criticism, which can be challenging for my inner critic to take and can lead to me getting defensive.

I now try to counteract this with a practice of appreciation. Each day, I try to identify what’s going right. If I can end the thought (unsarcastically) with “so I’ve got that going for me,” I consider it a win. When my perfectionism and defensiveness hurts others, I try to open myself to hear how my behavior impacted them. Then I apologize and figure out how I can put things right.

My observations of white supremacy culture in organized Humanism and Ethical Culture

I’ve observed white supremacy culture characteristics while working with/in Humanists International, the American Humanist Association, and the American Ethical Union. The associated examples are real-life observations and quotes from atheists, humanists, and Ethical Culturists during my work:

Perfectionism

Folks within these organizations talk to others about a person's inadequacies or their work without ever talking directly to them.

Ex. There is a lot of gossip and talking behind people’s backs. Admittedly, some of this is out of fear that the person will not receive feedback well (white fragility). But a lot of it comes down to fear of open conflict.

There is little to no learning from mistakes. Little time, energy, or money is put into reflection, or identifying lessons learned that can improve practice. See: only one right way.

Ex. I have seen marginalized people mistreated repeatedly by these organizations because there is little to no effort to improve practice. And the existing measures are largely performative to “check a box.”

Little appreciation is expressed among people for the work that others are doing, and appreciation is usually directed to those who get most of the credit anyway.

Ex. Some people in the organizations are willing to do the difficult work of dismantling white supremacy but are met with resistance and little appreciation by those in power.

Sense of Urgency

A continued sense of urgency makes it difficult to be inclusive, encourage democratic and/or thoughtful decision-making, think long-term, consider consequences, or learn from mistakes.

Ex. Scheduling special board meetings in between regular board meetings to address things that do not need to be discussed in a special board meeting.

Ex. Undemocratic decisions are made in the name of a contrived urgency.

These organizations frequently sacrifice allies or potential allies for quick or highly visible results.

Ex. Fundraising for a Nigerian man who has been in prison for blasphemy for three years and misrepresenting how much of the funds are actually going to the imprisoned man and his family while privileged people profit from the fundraisers.

Defensiveness

Because of either/or thinking, criticism of those with power is viewed as threatening or inappropriate (or rude).

Ex. My criticism of Humanists International leadership for their white privilege and negligence around pandemic safety (which resulted in a COVID outbreak) was treated as a threat (called “uncollegial”), and they removed me less than a week later.

People respond to new or challenging ideas with defensiveness, making it very difficult to raise these ideas.

Ex. “Is addressing white supremacy culture really that big of a priority for our organization? Aren’t there more important things?”

Ex. “Is addressing clergy misconduct really that big of a priority for our organization? Aren’t there more important things?”

Ex. Sealioning is regularly employed to wear down the people who raise new or challenging ideas in these organizations.

The organization's energy is spent working around defensive people and ensuring their feelings don’t get hurt.

Ex. These organizations work hard to protect the feelings of people who have not confronted their white fragility.

Ex. There is comfort in criticizing defensive people behind their backs. Still, when presented with an opportunity to bring criticism to the person in question, most folks aren’t brave enough to say anything.

In all three organizations, white people spend energy defending against charges of white supremacy culture instead of examining how it’s actually happening. There is a more substantial concern with reputation than putting right harms done.

Also, in all three organizations, leaders perceive calls for change as personal attacks. Their defensiveness creates an oppressive culture where people feel they cannot make suggestions – or when they do, they are ignored.

Worship of the Written Word

Those with strong documentation and writing skills are more highly valued, even in organizations where the ability to relate to others is key to the mission.

Ex. My contributions as a writer and good note-taker are more highly valued than those as a young international humanist activist.

Ex. When a harmful situation arises that bylaws, policies, and written agreements do not provide clear instructions on how to address, it either paralyzes leadership from taking any action at all or takes authoritarian liberties rather than turning to democratic and inclusive decision-making processes. There has been little to no accountability for board trustees and Leaders who act inappropriately and repeatedly cause harm to workers, volunteers, and partners.

Only One Right Way

There’s a belief that there is “one right way” to do things, and once people are introduced to the right way, they will see the light and adopt it.

Ex. Multiple practical suggestions to pay respect to volunteer time were shot down, such as not having many multiple hours-long meetings and putting time limits on each agenda item.

Ex. There is enormous resistance and fear around trying Restorative Justice.

When someone does not adapt or change, then something is “wrong with them.”

Ex. People in these organizations have named me a “problem” because I challenge the status quo. They simultaneously want to grow and push people out that don’t conform to “the only one right way.”

Ex. I have witnessed many young people, people of color, queer people, and disabled people “othered” and pushed out of these organizations because they do not conform to harm-inducing elements of the status quo.

There’s a similar quality to the missionary who does not see value in the culture of other communities and only sees value in their beliefs about what is good.

Ex. Humanists International regularly holds meetings in Europe with the excuse of “cost savings” and hosts meetings virtually during times most convenient for Europeans.

Ex. The framework within both organized humanism and Ethical Culture is a “charity” model rather instead of solidarity or partnership. This is an old colonizer/settler mental model that is rooted in white supremacy culture and racism.

Ex. Folks in the Ethical Culture movement regularly invoke the “No True Scotsman” fallacy to other and discredit people who do not identify as Ethical Culturists (despite the motto being “deed before creed”).

Ex. Humanists, atheists, and Ethical Culturists often move through the world with a sense of superiority exuded through intellectualism, despite claiming to hold values that advocate for equality. See also: paternalism.

Paternalism

Decision-making is clear to those with power and unclear to those without it. Members of organizations feel like they’re in the dark about decision-making by leaders but are significantly impacted by those decisions.

Ex. Firing the AHA Executive Director suddenly but publicly framing it as a “she left her position.”

Ex. Outright refusing to help me understand how and why I was removed from my role as President of Young Humanists International despite how much it devastated me.

Those with power assume they can make decisions for and in the interests of those without power.

Ex. “Anya, you are not ready yet to run for the AEU Board. You’re too young. I think you should step down from your candidacy. Take a few years.”

Ex. “Jé, you just have to wait, and you will eventually get the position you’ve been working on getting for eight years already in this organization.”

Those with power often don’t think it is necessary to understand the viewpoint or experience of those for whom they are making decisions.

Ex. When faced with a community member who has been harmed, the first reaction is to demand evidence to make decisions for the person who has been harmed rather than first acknowledging harm has occurred and validating the pain of a community member. Decisions are made without the harmed person – if, and only if, those in power determine enough harm has been done.

Either/Or Thinking

Mere education about white supremacy culture is ironically met with either/or thinking pushback. In my response to my article, What is White Supremacy Culture?, a white man misinterpreted white supremacy culture as equating whiteness with badness and Blackness with goodness.

With either/or thinking, there is little room for nuance, and there is often an effort to simplify complex things. This frequently happens in the board room and is closely linked with a “sense of urgency.”

Ex. “We cannot attract more people of color and young people because we have poor marketing. Either we get better marketing for this organization, or we fail.”

Ex. “We aren’t fundraising enough, and that’s why we’re failing as an organization. Either we make raising money top priority and nothing else, or we fail.”

Power Hoarding

Despite these organizations advocating for democracy, there is little value in sharing power in practice. Power is seen as limited, and those with it feel threatened when anyone suggests changes in how things should be done in the organization. Those in power often feel suggestions for change are a reflection of their leadership.

Ex. People tend to stay in positions of power for longer than they should despite conflicts of interest they hold.

Ex. There is an appallingly loose interpretation of the term “conflict of interest.”

Ex. These organizations have very few contested elections, despite emphasizing the democratic process.

Ex. Suggestions for change are often taken personally by those in power, and the shift then focuses on the feelings of those in power.

Ex. Efforts to collaboratively create board agendas were stopped so one individual could control agenda-making.

Those with power don’t see themselves as hoarding power or feeling threatened.

Ex. Pointing out power hoarding to people who are power hoarding in these organizations usually results in them brushing it off or refusing to acknowledge it.

Those with power assume they have the organization's best interests at heart and assume those wanting change are ill-informed (stupid), emotional, and inexperienced.

Ex. Coaching was offered to a board president, and it was taken as an insult.

Ex. Attempts to reduce inefficiency on the board by prioritizing issues that are not administrative or operational in nature have been thwarted by leadership.

Ex. The board president argues for inclusion, only to then exhaust trustees and discourage any hope of moving the organization.

Fear of Open Conflict

People in power fear expressed conflict and try to ignore or run from it. When someone raises an issue that causes discomfort, the response is to blame the person for raising the issue rather than to look at the issue which is causing the problem.

Ex. Those who speak up as critical voices to power are demonized. I have observed this in all three organizations.

There is an emphasis on being “polite” while at the same time being deeply offensive to those who raise criticism. Folks often equate raising difficult issues with being impolite, rude, or out of line.

Ex. This is a prominent feature of the Ethical Culture movement. There is a focus on being “nice.” There is a lot of pearl-clutching when systemic problems are named and a lot of defensiveness that causes harm to those who name the issues.

Ex. If someone makes a valid criticism that leadership takes personally, the criticism is framed as being “impolite” or even hurtful. (White fragility on display is also part of white supremacy culture).

Individualism

There is a lack of accountability. And when there is accountability, it is not applied equally.

Ex. These organizations are not fully transparent about budget matters and do not try to help community members understand.

Ex. Accountability practices are wildly inconsistent, and those who hoard and abuse power are often shielded from being held accountable.

Ex. Growth is stifled because people continue to leave due to a lack of accountability or sweeping things under the rug.

There is a desire for individual recognition and credit – many egos in these organizations. Competition is more highly valued than cooperation, and where cooperation is appreciated, little time and resources are devoted to developing cooperation skills.

Ex. “I’ve taken it upon myself to make this decision for the board.”

Ex. There is a culture of distrust in these organizations because of how competitive people become to push their agendas.

Ex. There is a general belief from people in positions of power in these organizations that they do not need further education or self-development – that they are above it.

“I’m the only one.”

In the same vein of individualism and “only one right way,” many leaders in these organizations believe they are the only ones who can get things done “right” and thus have little to no ability to share power.

Objectivity

There is a belief in atheist, humanist, and Ethical Culture communities that there is such a thing as being objective or “neutral.” There is also a belief that emotions are inherently destructive and irrational and should not play a role in decision-making or group process. People who show emotions are invalidated. There is impatience with thinking that does not appear “logical” or linear.

Ex. I’ve observed both my emotions and the emotions of others being invalidated in my time with Humanists International, the American Ethical Union, and the American Humanist Association.

Ex. “Anya, you’re really overemotional. Do you want to leave the meeting?”

Ex. I’ve seen other people who also show emotion – most often white people who represent some form of status quo – referred to as “neutral.”

Right to Comfort

There’s a strong belief that those with power have a right to emotional or psychological comfort, and those who cause discomfort are often scapegoated.

Ex. “You hurt _____(person in power)’s feelings; this is a serious offense.”

Ex. Nadya Dutchin, Jé Hooper, Rachel Pfeffer, and I are just a few of the people who have been treated as scapegoats for encouraging people in power to pivot from the status quo to address white supremacy culture. These folks were making recommendations to ensure these organizations thrive and grow more collaboratively and less harmfully.

Equating individual acts of unfairness against white people with systemic racism that daily targets people of color.

Ex. The white fragility in all three of these organizations is a serious problem. Many people in these movements lack the emotional intelligence to recognize when filling the space with their fragile emotions to drown out valid criticism. This is a serious problem for people of color and for the growth and survival of the humanist and Ethical Culture movements.